The Profile Dossier: David Swensen, the Greatest Institutional Investor of All Time

"Never underestimate the gullibility of large pools of money."

David Swensen was a pioneer in the world of investing.

The legendary money manager, who passed away in May after a battle with cancer, is credited for revolutionizing the way that universities invest their assets. Swensen was the chief investment officer at Yale's endowment—the multibillion-dollar pool of money that makes up Yale’s fortune.

In his three-decade career, he grew the university's endowment from $1 billion in 1985 to $31 billion in 2020. The results speak for themselves as he is largely considered to be one of the greatest investors of our time.

“He’s right up there with John Bogle, Peter Lynch, [Benjamin] Graham, and [David] Dodd as a major force in investment management,” says Byron Wien, a longtime Wall Street strategist.

When reflecting on his legacy, Swensen was particularly proud that the endowment allowed Yale to dedicate resources toward student financial aid, faculty salaries, and university research.

“One of the things that I care most deeply about is that notion that anyone who qualifies for admission can afford to go to Yale, and financial aid is a huge part of what the endowment does,” he said in 2014.

What made Swensen so successful? He pioneered a template for long-term investing that is now widely known as “the Yale model.” It's been mimicked by other institutions, including Princeton, the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, and Bowdoin College.

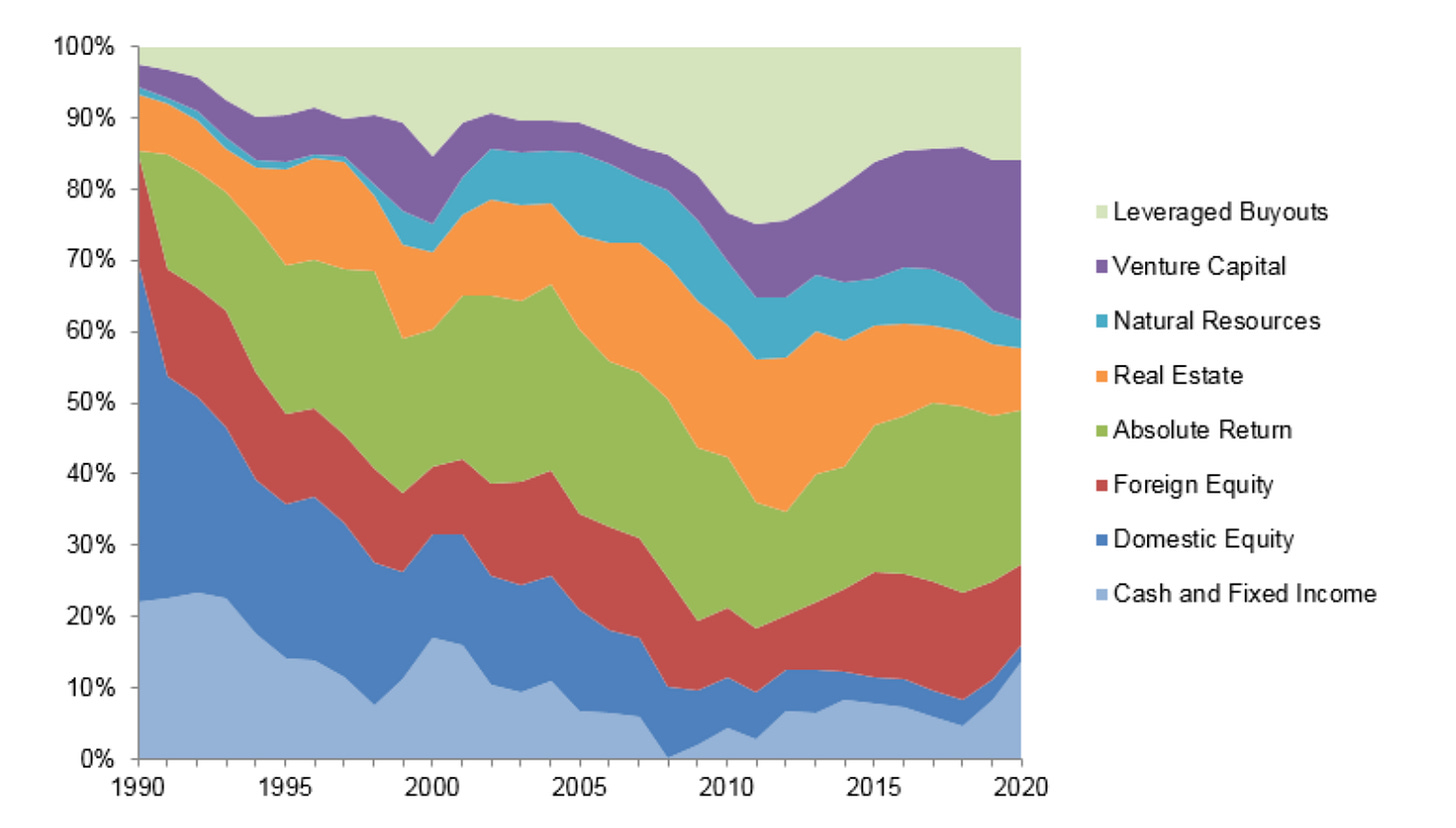

Swensen's investment approach was novel and contrarian for its time. It divided Yale's endowment portfolio into five or six equal parts and invested each in a different asset class. The model focused on broad diversification and doubled down on equities and a significantly higher allocation for alternative assets, such as venture capital and private equity.

Before he arrived at Yale, he was also considered a pioneer on Wall Street. Swensen made history in 1981 after he structured the first-ever "swap agreement," which allowed IBM to hedge its exposure to Swiss francs and German marks in a deal with the World Bank. It led Lehman Brothers to hire him to run the firm's swap group for three years.

When Yale approached him about becoming the head of its billion-dollar endowment, he didn't hesitate to take the job even though it required him to take an 80% pay cut. He was only 31 years old when he started working at Yale, his alma mater where he would spend the remainder of his career.

“When I see colleagues of mine leave universities to do essentially the same thing they were doing but to get paid more, I am disappointed, because there is a sense of mission,” he said. “People think working for something other than the most money you could get is an odd concept, but it seems a perfectly natural concept to me.”

Here's what we can learn from Swensen about his innovative philosophy, the role of active and passive investing, and how we can better prepare for retirement.

READ.

On becoming an investment legend: Swensen was a legend at Yale. It’s largely thanks to him that the university can woo star scholars and that its admissions can be need-blind. This must-read profile details how he built a template for long-term investing now known as “the Yale model.”

On the allure of the Yale Model: Swensen proved he could beat the market, and others wanted to as well. Even though his institutional investment machine has been often imitated, it has almost never been replicated. Legions of U.S. nonprofit CIOs claim they’re “doing the endowment model.” They’re not. This feature answers the question: "Swensen's philosophy is great for Yale, but is it horrible for investing?"

On his investment strategy: In his book Pioneering Portfolio Management, Swensen outlines his unconventional approach to institutional investing. Just note that this book is wonky, dense, and technical and meant for those working directly in finance or active fund management.

On developing a contrarian investment alternative: In his 2005 book, Unconventional Success, Swensen gives readers asset allocation tips and explains why the for-profit mutual-fund industry consistently fails the average investor. He wrote it to provide guidance for improving the personal investor's financial future.

LISTEN.

On how to invest for retirement: Even though he managed a complex portfolio for Yale, Swensen had also become passionate about trying to teach individual investors how best to invest for retirement. In this podcast, Swensen describes his basic formula for creating an investment portfolio likely to give you good returns while still managing risk.

WATCH.

On the overview of his approach: Swensen opens this guest lecture with a critique of his investment approach from Barron's magazine after the 2008 crash. "I think when it was successful, it was 'The Yale Model,' and when it failed, it was 'The Swensen Approach,'" he jokes. This is a master class on the power of asset allocation — and what to do when your wildly successful strategy hits a rough patch.

On the automation of capital allocation: In this interview, Robert Rubin asks Swensen the following question: "What about the notion that over time, AI and machine learning are going to replace the David Swensens of the world?" To which Swensen replies with: "Usually I'm not glad that I'm 64 years old and nearing the end of my career and not the beginning but that question makes me glad of those facts." He goes on to explain why he's not a fan of quantitative approaches to investing. This is a fascinating, wide-ranging conversation.

POLINA'S TAKEAWAYS.

Diversification wins out in the long-term: When Swensen arrived at Yale, he saw that the endowment held more than 75% of its capital in U.S. stocks, bonds, and cash. He thought this was a mistake because it indicated the portfolio was not adequately diversified. In essence, he saw Yale as taking too much risk by putting too much money into U.S. stocks & bonds while missing out on investment classes that included foreign stocks, real assets, private equity, and hedge funds. By diversifying beyond U.S. stocks, Swensen was able to seek opportunities in less liquid, less efficient markets. Remember, diversification can fail us in the short term due to day-to-day volatility, but it's ultimately the one he believed wins out in the long-run.

Rebalancing is important during financial downturns: What is an investor to do during times of economic trouble? As a long-term investor, Swensen saw economic downturns as an opportunity to rebalance their portfolios. In other words, even when it seems like the world is falling apart and markets are swinging violently, it takes courage to buy what’s on sale, even at deep discounts. He knew this was difficult to do in times of crisis. "If you talk to a businessman, a businessman is going to feed the winners and kill the losers," he said. "But in the investment world, when you've got a winner you should be suspicious about what's next. And if you've got a loser, you should be hopeful—although not naively hopeful."

The boring approach may be the most rewarding: Swensen believed that there are two types of investors: those who can make high-quality active management decisions and those who can't. (Active investing is a hands-on approach whose goal is to beat the stock market index whereas passive investing is a hands-off approach that tracks a market-weighted index or portfolio.) "Almost everybody belongs on the passive end of the continuum," he said. "A very few belong on the active end. But the unfortunate fact is that an overwhelming number of investors find themselves betwixt and between." It's in that in-between place where people like you and me end up paying high fees to a mutual fund or a stockbroker. "And they end up with disappointing net returns," he adds. As un-sexy as it may seem, the passive approach is the one best suited for most individual investors who don't have the time or expertise to manage a portfolio actively.

Remember that money without purpose is meaningless: Although Swensen made billions for Yale, he emphasized that purpose is what drove him on a daily basis. He could've left the university and made significantly more money for himself elsewhere, but he was proud that Yale's growing endowment helped contribute to financial aid for the students.

QUOTES TO REMEMBER.

"Never underestimate the gullibility of large pools of money."

“Only foolish investors pursue casual attempts to beat the market, as such casual attempts provide the fodder for the skilled investors’ market-beating results.”

"I believe that the greatest teachers create thinking students."