How Gwyneth Paltrow Turned Goop Into a $250 Million Obsession

Here's how Paltrow’s once-mocked ideas about health and wellness became part of mainstream culture.

This guest post was written by Ali Montag, a writer based in Austin who authors Letters from Home & Away. Below, Montag breaks down Paltrow’s always-controversial brand strategy that’s turned her into a business powerhouse.

—

How Gwyneth Paltrow Turned Goop Into a $250 Million Obsession

By Ali Montag

At some point in 2021, I switched my morning podcast from The Daily, a show by The New York Times about politics and current events, to Smartless, a podcast by three comedians, about, quite literally, becoming less smart. I was no longer in the mood for facts. I was tired. I didn’t want to think—I wanted to be entertained.

The show’s celebrity hosts offered background noise while I scrambled my eggs. When I listened to the episode with Gwyneth Paltrow, an interview in which Paltrow talked about the things we all talk about (her work, her kids, her husband) it went down like my morning coffee: Pleasant, sweet, and not particularly memorable. At one point, she mentioned she’s been a little less healthy during the last year, eating bread and having whiskey on weeknights. The toast popped in my toaster. Who hasn’t? The episode ended and I thought nothing of it.

Then, I opened Twitter. There it was. Trending: Gwyneth Paltrow. Why? I clicked again. Woah: outrage, and lots of it. “Gwyneth Paltrow broke down and ate bread during quarantine,” The Guardian exclaimed. The reactions were swift and merciless, full of antipathy for wealthy women and their whining. “Gwyneth talking about a weakness for bread while people are sick and dying doesn’t read particularly well,” Vogue surmised. The issue was the contrast: Our world was falling apart. And she was stressed about eating bread?

To the Internet, it seemed as if Paltrow had implied her life was so perfect—so full of meditation and intention and juice cleanses and vitamins and antioxidants and all the other things sold by Goop, her $250 million lifestyle business—that even a global health crisis could barely make a dent. Just the carbs, that was all.

But she didn’t actually say that. In fact, she didn’t really say anything. She just chatted a bit about her life and her coffee mug and the bone broth she drank from it. Sure, her chit chat sounded different than ours might. She’s rich, yes. She’s healthy, yes. But none of that was new.

So why all the backlash? And why does it matter?

To understand Paltrow, her success, and the staying power of Goop, an absurdly important brand in health, beauty, and wellness, we have to understand attention. This is the attention economy, after all: Politicians drum up support on Twitch and win elections on Twitter. Tech founders write on Substack. Celebrities sell lipstick on Instagram. Everything is a funnel.

Monetizing eyeballs

When Paltrow launched Goop as an email newsletter in 2008, using off-the-shelf software and writing her lists of recommendations, recipes, and product reviews for five years for free, she became an early student of the attention economy. She learned that backlash, which follows her relentlessly, doesn’t have to be the sunk cost of celebrity. It can be part of the plan.

“I can monetize those eyeballs,” Paltrow told a group of Harvard business students in 2018.

In the early years of Goop, which sells everything from detoxifying superpowders to $1,300 diamond rings, Paltrow coined the term “contextual commerce.” The Wall Street Journal defined it as the process by which “potential Goop customers are flooded with newsletters, blog posts, print magazines, conferences, events, podcasts and Instagram ads that surround Goop products in a cocoon of content.” Before plenty of other CEOs caught up, Paltrow understood: attention would be the most important ingredient in the modern commerce recipe.

In that context, Paltrow’s lighting-rod-like public perception wasn’t a risk, it was an advantage.

Whatever you feel about Gwyneth, you feel something. Perhaps you rolled your eyes at the idea of conscious uncoupling, or perhaps you were outraged at the marketing of jade eggs. Perhaps you found it annoying that in a single column, a person could promote both a detox cleanse and a Saturday night cigarette for “the right amount of naughty.”

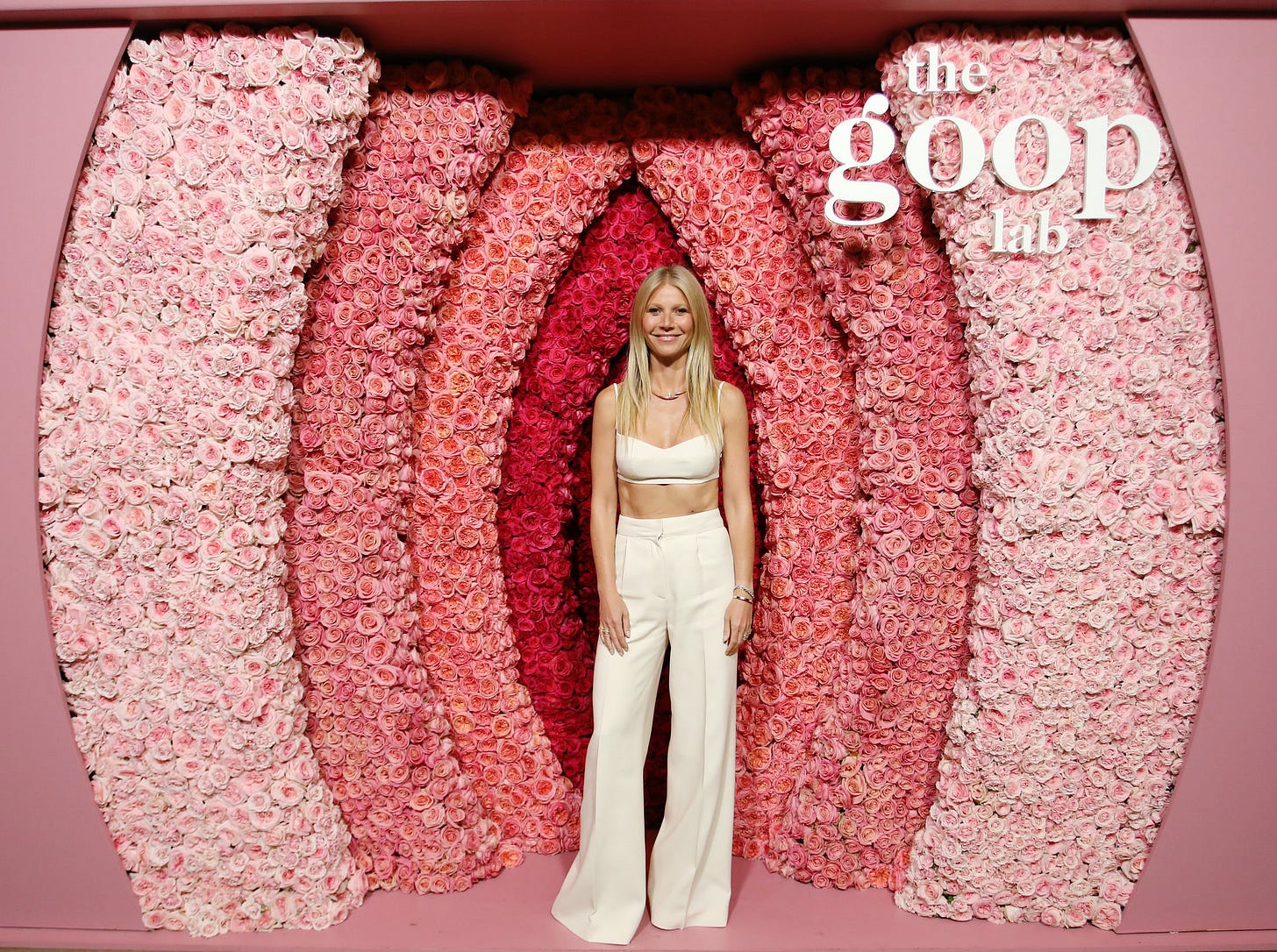

Perhaps you were horrified by her Netflix show, “The Goop Lab,” which covered topics like psychedelic mushrooms, breathing exercises, cold exposure, and anti-aging. Perhaps you were a little bit intrigued.

It doesn't matter. It doesn’t matter how you feel about Paltrow—or whether or not the products work, or whether psychics can talk to the dead, or if “energy work” is a reasonable way to heal trauma—as long as you’re paying attention. In the end, attention wins.

“I have always been a person who says what I believe to be true and I have always been unafraid to say things that might be provocative,” Paltrow wrote in 2020. “I have talked about many things over the years that people called me crazy for: yoga, reiki, macrobiotics, gluten-free food, anything about vaginas... The negativity that surrounded each one lives on on the internet. It became just part of the cycle: I, or we at Goop, introduce something unfamiliar, there’s a big reaction, before gradual cultural adoption.”

Paltrow is just expressing her curiosity, asking questions and offering her perspective. If that provokes a backlash—well, that’s kind of the point.

“The Gwyneth Paltrow business story is not about Gwyneth Paltrow as much as it is about your reaction to Gwyneth Paltrow,” The New York Times’ Taffy Broddesser-Akner explained.

And there’s plenty to react to: Paltrow is the queen of wellness, but her favorite food is french fries. Mario Batali once said, “She eats like a truck driver.” She launched her newsletter in the height of the Great Recession in 2008, but her first recommendations were for an $1,850 Hermes watch and a $1,350 Mulberry bag. She married Brad Falchuk, but decided to spend the next year living separately anyway. It’s catnip for the Internet. There have been at least 100 takedowns written about Gwyneth Paltrow. And yet, she’s still illuminating our iPhone screens, and Goop is only gaining subscribers.

There are also questions about efficacy. (Lots of questions about efficacy.) How much of this “wellness” stuff is real?

In the first episode of “The Goop Lab,” Goop’s former chief content officer Elise Loehnen explained the brand’s mission this way: “What we try to do at Goop is be open minded and explore ideas that may seem out there or too scary, so that people can have access to the information and make up their own minds.”

It’s not journalism, she contends, it’s exposition. "We're just asking questions! We're not giving advice!" Hearing her quote, I briefly thought of the early days of the Trump campaign in 2015, the tossing out of unfounded ideas and errant theories. "We didn't say it was true! We're just saying maybe it is!"

In those days, when Jeb Bush was considered the most likely contender against Hillary Clinton, establishment pundits were dismissive of Trump. The campaign didn’t make sense: “He’s a Republican, but he’s pro labor?” “He wants to cut taxes, but increase federal spending?” “He’s courting Evangelicals, but his house is made of gold?” “He can’t be a conservative. He’s from Manhattan!”

It’s no surprise a tech journalist, someone steeped in platforms and algorithms and exponential growth, caught what was happening. It didn’t matter that he was confusing, Kara Swisher noted. That was the point. He was interesting. “When he was using Twitter, I remember thinking, ‘Woah. That’s smart,’” she said. In the attention economy, the more outrageous, the better.

Amplifying the ‘extraordinary’

Surrounded by a constant barrage of news, tweets, statistics, and opinions, it’s not the most accurate or technically precise information that wins out. It’s the most engaging. Who wants to read a peer-reviewed study on efficacy when YouTube videos are just so darn nice to watch?

Consider this reporting from Vice: “In 2018, a team of researchers at MIT published the most comprehensive study to date on how mistruths spread online, based on a survey of about 126,000 rumors shared on Twitter by roughly 3 million users over the span of 11 years. They found that falsehoods consistently beat out the truth on the platform, spreading ‘significantly farther, faster, deeper, and more broadly than the truth in all categories of information.’ False claims are 70 percent more likely to be retweeted than true ones, they found, and far more likely to go viral.”

In summary: “People are more likely to amplify something extraordinary.”

What Goop is doing may not win Paltrow the presidency, but it is extraordinary. Sometimes confusing, outlandish—yes—but extraordinary. And it works: Paltrow’s once-mocked ideas about health and wellness are now a part of the culture: How many of your co-workers have dabbled with intermittent fasting? Shrooms? Cleanses? Thank Gwyneth Paltrow.

In capitalism, if no longer in politics, there is an inevitable pivot to the middle: There are no more jade eggs at Goop. The company added a team of scientists and health experts to fact-check claims. The $4,000 Cartier watches are sold next to more accessible items like vitamins and sunscreens under $50. Goop is launching retail partnerships and Paltrow is angel investing.

But it’s worth asking: What comes next? For the next upstart brand aiming to push the boundaries of wellness, what extraordinary content will be required to capture an audience’s attention? What could possibly out-Goop Goop?

Will the pendulum swing even farther into dubious health claims, ringing digital cash registers for the most concerning corners of TikTok? Or will it swing back toward the staid professionalism of a doctor’s office? Will pharmaceutical companies be the only businesses larger than “wellness”? Will we trust YouTubers with organic elixirs or doctors with pill bottles? (Read Mark Penn’s “Microtrends Squared” for an argument on why the answer might be both.)

No one knows. Certainly I don’t. But it isn’t a question for celebrities to answer—It’s something to ask ourselves.

Re-envisioning the attention economy

At home, scrolling Instagram in the dark, we want to see things that are extraordinary. We want to feel extraordinary. More than anything, we just don’t want to be bored. Even the most ardent news junkies find ourselves queuing up celebrity banter at breakfast time. It’s human nature: We like good stories.

But we need to beware of funnels. The attention economy (or its new iteration, “the creator economy”) shows no sign of slowing. As the platforms that architect our digital lives seek to capture and monetize every iota of our attention, there are funnels and trapdoors lurking everywhere. Everything we click can become a slippery slope. Since starting to write this piece, poking around on the Goop website, I’ve asked myself at least five times: “Do I need vitamins with elderberries and antioxidants? Should I get a moisturizer with hyaluronic acid? What if I tried to go vegan for a week? G.P. does look really good!”

But I don’t need any of those things. And I like eggs! And yogurt! I’m fine. I remember this as soon as I shut the laptop. The funnels go away when the screen shuts off.

It’s important to remember: Every action we take online is a choice. If capturing attention was the skill that defined the last decade, discernment will be the skill that defines the next. We are in control. It’s our responsibility to be careful with the way we invest our time, money, and attention.

We’re all allowed to say, “No thanks Gwyneth. Not today. But you do look great!”

> But we need to beware of funnels. The attention economy (or its new iteration, “the creator economy”) shows no sign of slowing.

Genuinely curious.. and might be slightly off topic

What’s wrong with the creator economy? I have my own criticism but I want to hear yours first