Author Rob Henderson on Why We Hold ‘Luxury Beliefs’ and Develop ‘Status Anxiety’

Author Rob Henderson recounts growing up in foster care, attending elite universities, and pioneering the concept of “luxury beliefs.”

“My name is Robert Kim Henderson. Each of my three names was taken from a different adult … These three adults have something in common: All abandoned me.”

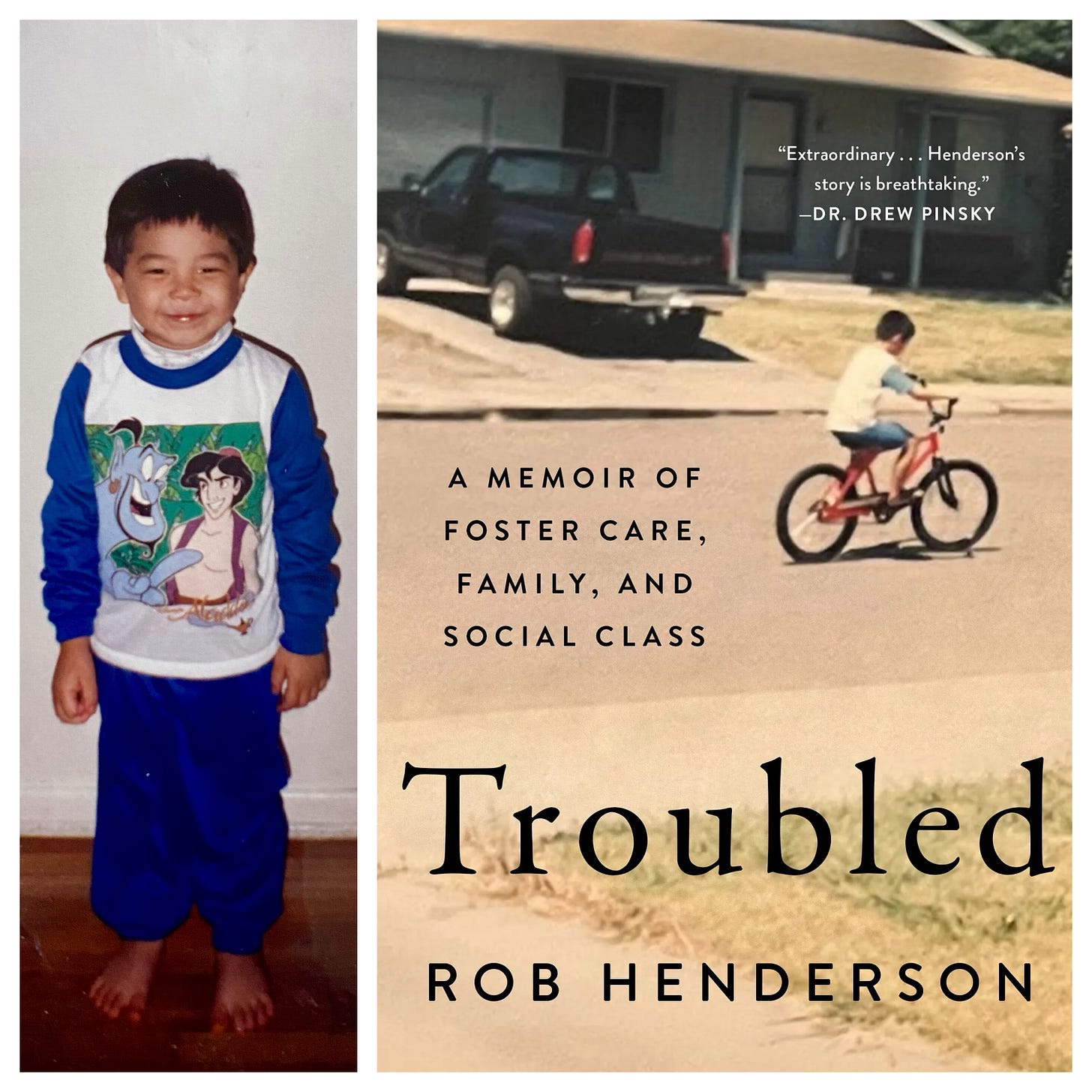

This is the powerful opening to Henderson’s new memoir, Troubled: A Memoir of Foster Care, Family, and Social Class.

Needless to say, Henderson’s early life was turbulent.

“Robert” was the name of his biological father, who abandoned him and his mom when Henderson was just a baby. “Kim” was his birth mother’s family name. She succumbed to drug addiction soon after Henderson was born, and he hasn’t seen her since he was a toddler. “Henderson” is the last name of his adoptive father, who severed ties with him after he divorced his adoptive mother.

Henderson’s earliest memory is from when he was three years old living with his birth mother in a Los Angeles apartment.

“It was a one-bedroom apartment, and [my mom] would tie me to a chair with a bathrobe belt while she would go into her room and get high,” Henderson, 33, said in an interview with The Profile. “Eventually, some neighbors heard me crying and yelling, and called the police. [The police] took me, arrested her, and put me into [foster] care.”

Divorce, tragedy, poverty, and violence dominated Henderson’s adolescence, but you would never know this from looking at his resume. He joined the Air Force at 17, went to Yale for undergrad, and earned a PhD at Cambridge.

In his new book, Henderson recounts growing up in foster care, attending elite universities, and pioneering the concept of “luxury beliefs.” These so-called “luxury beliefs,” Henderson says, are ideas and opinions that confer status on the upper class while inflicting costs on the less fortunate.

“A core feature of a luxury belief is that the believer is sheltered from the consequences of his or her belief,” Henderson says. “People still buy material items to signal their status, but because they've become a noisier signal over time, people are starting to signal their status with their beliefs by having unusual or peculiar ideas.”

In this conversation, Henderson discusses the events of his early life, the prevalence of victimhood in today’s society, and whether it’s possible to opt out of the status game.

(Here’s how I described Rob’s new memoir, Troubled: “‘Troubled’ is impossible to put down. Rob’s raw and intense account of his childhood reveals that there are two Americas: one that rewards you for perpetuating 'luxury beliefs' and one that pays the price. Rob is a master storyteller, and his memoir acts as a mirror in which we can all see our own imperfect reflections. One of the best memoirs I’ve ever read.”)

—

This Q&A has been lightly edited for clarity and length.

(Below is an excerpt, but I encourage you to listen and watch to the full interview below.)

🎧 LISTEN.

🎬 WATCH.

You’ve said that your earliest, clearest memory comes from when you were 3 years old. What is the memory?

HENDERSON: In that first memory, I was three [years old], and I was clinging to my birth mother's lap. I'm sort of burying my face in her lap, and I come up for air, and I see these very tall men in black clothing. I can tell they want to separate us.

I'm just clinging very tightly to my mother hoping that, maybe, if I bury my face and wait long enough and cling tight enough that these guys will just go away. And then the memory kind of cuts off there.

Then, the next part of it is that I'm sitting on a bench in this very brightly lit hallway — this long, wide hallway. My mother's next to me, and I'm drinking this carton of chocolate milk, and I sneeze and kick my legs, and the milk spills.

I'm upset and crying, and I look over at my mother, and she can't help me because she's wearing handcuffs. And the memory basically cuts off there.

Then, I go into this carseat being driven by my social worker going into my first foster home.

So it’s like three very vivid memories and they don’t flow smoothly, but that’s how upsetting and traumatic memories work. You have very sort of flashbulb memories — very vivid — but they don't always cohere perfectly.

How did you get to Yale University?

I was in the Air Force for eight years. I joined when I was 17, and I left when I was 25.

I had eight years of extreme, rigid structure, inculcating good habits, and learning self-discipline. So, the military equipped me with a lot of those those tools. As my enlistment was winding down, I visited the Education Center on base, which turned out to be very unhelpful.

I didn't get the best advice as far as what to do with the GI Bill, which is this tuition program that essentially pays for 100% of college tuition and supplies a living stipend to all veterans who served after 9/11. You can basically get to go to college for free.

So I had the financial part figured out, but then I needed to figure out the actual application part. No one in my family went to college. It was a completely new experience, so I didn't know anything. I didn't know how to get recommendation letters. There's all these things that if you're a first-generation student, no one really sits you down and tells you these things.

I googled around and eventually figured out how to get into this program called the Warrior-Scholar Project, which markets itself as an academic boot camp that teaches veterans how to get into college and be good college students.

I went through that program, and it turned out to be really helpful. Through that, I managed to get into Yale. In hindsight, even to this day, I still can't quite believe they let me in.

A lot of people will hear about your circumstances and see you as a victim. Are you a victim?

You know, I never thought of it that way growing up because everyone around me was living the same kind of life. So when it's just everyday life for me and people I grew up around, it wasn't like, ‘Oh, we’re being mistreated in some way.’ It’s just day-to-day survival. You don’t really think about yourself in those terms.

It wasn't until later when I actually got to campus that people started talking in these terms about being victimized or being mistreated or being oppressed. Once I started talking a bit more openly about my experiences, people would say, ‘Oh, you know, you were a victim,” or they used this term “victimhood.”

I think it's a very toxic mindset. I think for some of these people, their hearts are in the right place, but to sort of spread that idea and that mindset throughout society, I think is very debilitating.

I think it undercuts people's ambitions to get them to think of themselves as just a victim of circumstance with no agency and no free will.

Can you explain this term that you coined, “luxury beliefs?”

I coined this term ‘luxury beliefs,’ which I define as ideas and opinions that confer status on the affluent, while often inflicting costs on the lower classes and everyone else.

A core feature of a luxury belief is that the believer is sheltered from the consequences of his or her beliefs.

My claim is that luxury goods are gradually becoming a noisier signal of one's position in society. This isn't to say that they don't still confer status — they clearly do. People still buy material items to signal their status. But because they've become a noisier signal over time, people are starting to signal their status with their beliefs and their ideology by having unusual or peculiar ideas.

So my claim here is that luxury beliefs are the latest expression of cultural capital. A lot of these beliefs, you can only sort of express if you either attend an expensive college or you work the kind of job where you're not doing manual labor.

I coined the term ‘luxury beliefs’ in 2019, and I had no idea that within a few months, people would be calling to defund the police. You know, that was just not a prediction that I would have made. But that, to me, was like, ‘Wow, I coined this term ‘luxury beliefs’ and and suddenly people are saying, ‘Oh, we don't need police anymore.’” And then we saw the violent crime rate skyrocket.

It’s costless for [high-income Americans] to start saying, “Let's defund the police,” because it doesn't directly harm them. White Democrats were the most supportive of defunding the police while Black and Hispanic residents were the least supportive. But then, the picture we get from the prestige media and legacy institutions was, ‘Defund the police is the right thing to do.”

I want to challenge this a little bit. You grew up in some of these communities where people say that police target kids who aren't doing anything wrong, but just because they look a certain way. Do you find that that's the case?

I don't think so. It's true that the background of most criminals, they do tend to come from poor marginalized groups, but so are their victims. And the people who tend to commit the crimes are usually young men, more often than not, and their targets are often the elderly, or women, or people who are less likely to fight back.

I mean, if you don't arrest criminals, you're essentially victimizing the poor. But this is something I think that that is misunderstood in society. It seems like we get this distorted picture from the media where there are people who hold the view that the police are disproportionately targeting certain groups. But we almost never hear from the victims of crime, or the marginalized groups, who would like there to be more police.

How do you define the word ‘success?’

I guess what comes immediately to mind is: “Have you accomplished what you wanted to?’ So I don’t think there’s an objective measure of: ‘Check these boxes, and therefore, you're successful.’

If you wanted to go to college, and you went to college, I would call you successful. If you wanted to start a small business, and you managed to do it, I'd call you successful.

I think it's very much like, ‘Did you set out to do something? And did you actually accomplish it?’

Have you achieved the thing that you've wanted to achieve?

Not yet. I want to be a good dad. I think I would be, but I don't have kids, so I won't know until it happens.

As far as professional accomplishments, I guess I've pretty much done more than I would have expected, actually. So I've exceeded on that measure, but you know, I never had a dad. And that's something that I would like to be one day.