The Profile Dossier: Svante Pääbo, the Geneticist Unlocking the Secrets of our DNA

"Neanderthals are not totally extinct. In some of us they live on, a little bit.”

“I first thought it was an elaborate prank.”

This was Svante Pääbo’s reaction upon learning that he was the winner of the Nobel Prize.

Pääbo’s discoveries about the genomes of extinct hominins and human evolution earned him the 2022 Nobel Prize in physiology or medicine.

What does that mean in layman’s terms?

Well, Pääbo has spent his entire career digging into our past to help us to better understand our future. He has essentially cracked the code of human existence by doing the seemingly impossible: sequencing the genome of the Neanderthal, an extinct relative of the present-day human.

He wanted to answer the simple (and wildly complicated) every person has asked themselves at some point in their lives: What makes me me? Where do we come from and how are we related to those who came before us? What makes us uniquely human?

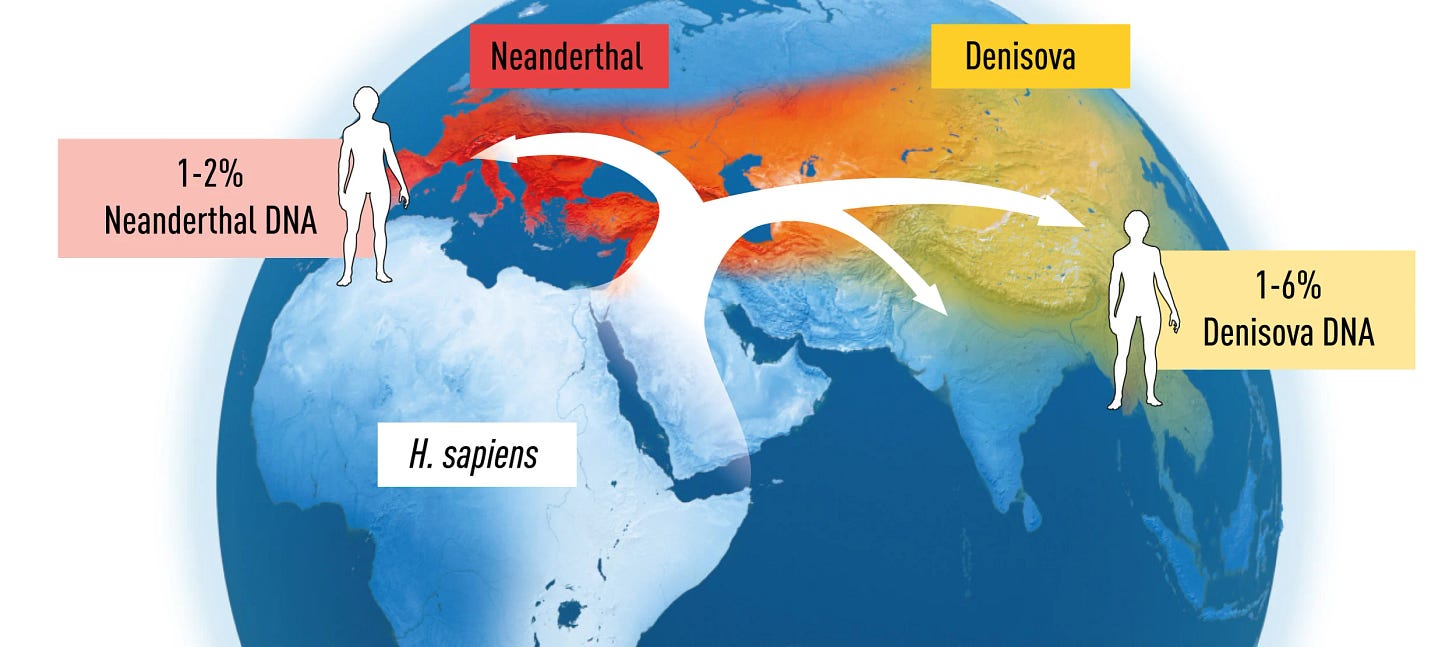

For context, we know that modern humans (Homo sapiens) emerged in Africa 300,000 years ago. About 70,000 years ago, groups of Homo sapiens migrated from Africa into the Middle East and to the rest of the world beyond.

Neanderthals lived in Europe and Asia 30,000 years ago before they disappeared, but because they had such distinctive features, it was widely believed that they did not reproduce with modern humans.

On the contrary, Pääbo and his team discovered the extent of the relationships we had with our extinct relatives. During the period that Neanderthals and Homo sapiens co-existed, they interbred all the time. In modern-day humans of European or Asian descent, approximately 1-4% of the genome originates from the Neanderthals.

The effort was anything but easy. As New Yorker writer Elizabeth Kolbert put it: Trying to extract DNA samples from ancient specimens is like “trying to reassemble a Manhattan telephone book from pages that have been put through a shredder, mixed with yesterday's trash, and left to rot in a landfill.”

Pääbo’s main discovery, which is arguably the most important, is that “purity” is a myth — we have long been mixing and migrating with other hominins. His research also found that it was mainly female Neanderthals who would leave their birth group to migrate to other tribes and reproduce.

The reason this is important is that there are Neanderthal genes that live on, and scientists can now begin to evaluate the gene variants of both human forms and make important discoveries about new (and old) diseases.

Even more interestingly, Pääbo’s conducted more research during the pandemic, and he found that having a specific Neanderthal gene variant may double the risk of dying from COVID-19. That variant is present in about 50% of people in South Asia, and about 16% of Europeans. He and his fellow researcher later found that there could be another Neanderthal gene variant that could actually protect against the virus, and it shows up in about half of people outside Africa.

“It is striking that this Neanderthal gene variant has become so common in many parts of the world. This suggests that it has been favourable in the past,” he says. “It is also striking that two genetic variants inherited from Neandertals influence COVID-19 outcomes in opposite directions. Their immune system obviously influences us in both positive and negative ways today.”

Pääbo has been conducting this type of research for years, so this is why the Nobel Prize recognition came as a surprise. When he received a call from a Swedish number he didn’t recognize, Pääbo assumed it was about … lawn maintenance. “I thought it had something to do with our little summer house in Sweden,” he said. “I thought, ‘Oh the lawn mower’s broken down or something’.”

Here’s what we can learn from the scientist who unmasked the lives of our ancient ancestors and helped answer some of the most fundamental questions of our humanity.

ith assistance from writer Simran Bhatia

READ.

On his winding journey to the top: Pääbo’s journey to becoming a respected scientist was full of hurdles. His ideas were farther along than the sequencing technology at the time and institutions did not want to sponsor his work. Nevertheless, Pääbo persisted for more than two decades, and his patience paid off. Fun fact: Pääbo requested a climbing wall and rooftop sauna during the construction of his current research facility.

On uncovering the truth of our ancestors: Before modern humans “replaced” the Neanderthals, they had sex with them. The liaisons produced children, who helped to populate Europe, Asia, and the New World. Not only did the two interbreed; the resulting hybrid offspring were functional enough to be integrated into human society. This profile is a must-read.

On the search for lost genomes: In his book, Neanderthal Man, Paabo recounts his efforts to unlock the secrets of the past. Beginning with the study of DNA in Egyptian mummies in the early 1980s and culminating in the sequencing of the Neanderthal genome in 2010, Neanderthal Man describes the events, intrigues, failures, and triumphs of these scientifically rich years through the lens of the pioneer and inventor of the field of ancient DNA.

WATCH.

On discovering the Neanderthal within us: In his TED Talk, Pääbo knits together the story of our existence from 30,000 years ago to present day, taking us on his path of research and what we can learn from our ancient ancestors. “I think the lesson is that we have always mixed,” he says. “We mixed with these earlier forms of humans, wherever we met them, and we mixed with each other ever since.”

On why modern humans are better: We see a different dimension to Pääbo in this fun, lighthearted conversation. He talks about his research in a digestible way, while interacting with Slash and Uma Thurman. Pääbo is open about his life as a secret child to a Nobel Laureate, and casually mentions his bisexuality. Whatever preconceptions you may have of scientists definitely don’t apply to Svante Pääbo.

POLINA’S TAKEAWAYS.

Our differentiator is transmitting knowledge to our kids: What differentiates humans from fellow hominins with whom we share the majority of our DNA? Pääbo believes only humans have the ability to transmit knowledge to our offspring from a very early age. We teach what we know to our children for the first few years of their life, and then the children build on top of that knowledge, so society can progress. Neanderthals didn’t teach their children anything, and neither do chimpanzees. But our tools and technology look vastly different today than they did 100 years ago, which makes us uniquely different from our ancestors.

It’s remarkable that we are human: Isn’t it absolutely mind-blowing to think that until very recently, we weren’t the only form of humans on the block? Pääbo thinks about this a lot. “I mean sometimes I think it’s interesting to think about if Neanderthals had survived another 40 thousand years, how would that influence us,” he says. “Would we see even worse racism against Neanderthals, because they were really in some sense different from us? Or would we actually see our place in the living world quite in a different way when we would have other forms of humans there that are very like us but still different. We wouldn’t make this very clear distinction between animals and humans that we do so easily today.”

QUOTES TO REMEMBER.

"Neanderthals are not totally extinct. In some of us they live on, a little bit.”

“It’s not wrong to make honest errors in science as long as you are ready to correct them when you realize. We learn from the setbacks and can move forward.”