What the Dramatic Origin Story of the Oxford English Dictionary Can Teach Us About Innovation

Some of the most important innovations have come from the world's most unlikely sources.

Some of the most important innovations have come from the world's most unlikely sources.

In 1857, the members of the Philological Society of London decided that existing English language dictionaries were incomplete. They thought up a crazy experiment: What if they could create a revolutionary new dictionary? It would be one that encompassed all sorts of words in the English language — from street slang to technical jargon. Most importantly, it would be less stuffy and pretentious than the official dictionary of the French language.

It was just as hard as you would imagine.

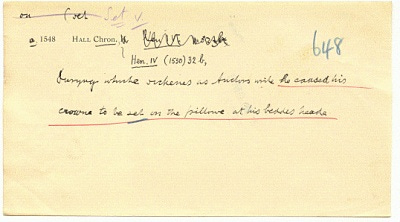

Each definition required supporting quotations: sentences from books, newspapers, and magazines that would show how the word could be used in various contexts. The team tasked to bring the dictionary to life spent years working on it, but eventually gave up as it turned into a disorganized disaster.

Then, in 1879, the Oxford University Press hired a professor named Dr. James Murray to take on the herculean effort. Murray understood he couldn't do it alone, so he published a request asking for volunteers to read books and submit the best sentences that portrayed the meaning of literally any word. His team would then sift through thousands of these slips looking for quotations that would illustrate each definition.

There was one contributor named Dr. William Chester Minor who would send in as many as 20 quotations per day to the dictionary editors. His submissions were really good and almost always accepted. He became one of the most prolific contributors to the dictionary.

James Murray was so impressed with his work that he decided to arrange a meeting with the mystery man. "I thought he was either a practicing medical man of literary tastes with a good deal of leisure, or perhaps a retired medical man or surgeon who had no other work," Murray said.

When Murray arrived at the location Minor had provided, he was stunned. Dr. William Chester Minor was a long-time patient at the Broadmoor Asylum for the Criminally Insane. The top contributor to the Oxford English Dictionary turned out to be a murderer.

Minor was an American, Yale-trained physician who had served as a surgeon-captain in the American Civil War. It was in his time treating soldiers that he began to show signs of paranoia. In the Army, he was given the task of punishing a soldier for "desertion" by branding him on the cheek with a "D." The punishment was considered a medical procedure, so it was up to Minor to carry it out. It is believed the incident played a major role in Minor's deteriorating mental health.

Since then, he became increasingly paranoid, carrying a handgun with him at all times and acting on an uncontrollable urge for sex by going to brothels every night.

On February 17, 1872, his paranoia materialized in an unfortunate way. Minor woke up in the middle of the night believing he saw an intruder in his room who ran out the door. He grabbed the gun from underneath his pillow, ran after him, and shot and killed a man in the street. Except the intruder existed only in his mind … Minor had killed George Merrett, a father and husband who was walking to work that morning.

A court found Minor not guilty on the grounds of insanity and sentenced him to the Asylum for the Criminally Insane. In a crazy turn of events, Eliza, Merrett's widow, went to visit Minor at Broadmoor a few times, bringing him books that helped build his collection.

Minor's life came to an end in a tragic way. After more than 30 years at Broadmoor, he was sent back to an asylum in the United States. He died 10 years later, and no obituary would ever mention his achievements and contributions to the Oxford English Dictionary.

I first learned about Minor's story when I read the book The Professor and The Madman a few years ago. When I finished it, there was one thing I couldn't stop thinking about: How many of us close ourselves off to some of the most fascinating conversations, ideas, and innovations simply because of the biases we hold?

Murray probably never thought that his most reliable source would be a patient in the Broadmoor asylum, but the best thing he did was ask volunteers from all walks of life to submit definitions and quotations. If he hadn't done that, an outsider as brilliant as Minor may have never been allowed to contribute more than 10,000 entries to the dictionary.

A more modern (and less extreme) example is that Flamin' Hot Cheetos wouldn't exist if a janitor at Frito-Lay hadn’t submitted his creation when the CEO asked for fresh ideas from all levels in the company. Janitor-turned-inventor Richard Montañez says, "Brilliance isn’t a diploma on the wall.”

The point is that innovation doesn't live inside elite institutions and fancy social clubs. More often than you think, it comes from "the poor, the unruly and the marginalized." And we all benefit when we open our worlds to the minds of people society has chosen to ignore.

One of the core tenets of The Profile newsletter is to improve your content. Sign up here:

Want more? Check out these great reads:

— How the World’s Most Creative People Bring Their Ideas to Life

— How the Language You Speak Influences Your Mental Frameworks

— 11 Practical Pieces of Advice I'd Give My Younger Self

— 100 Couples Share Their Secrets to a Successful Relationship

— How You Can Use "Hanlon’s Razor" to Avoid Petty Arguments

— 20 Business Power Players Share Their All-Time Favorite Reads

— The Science Behind Why Social Isolation Can Make You Lonely

— Meet Elon Musk, the Architect of the Future

— 3 Ways to Attract More Luck Into Your Life

— I quit my job at the start of the pandemic to launch a company. Here’s what I’ve learned in the first 90 days.