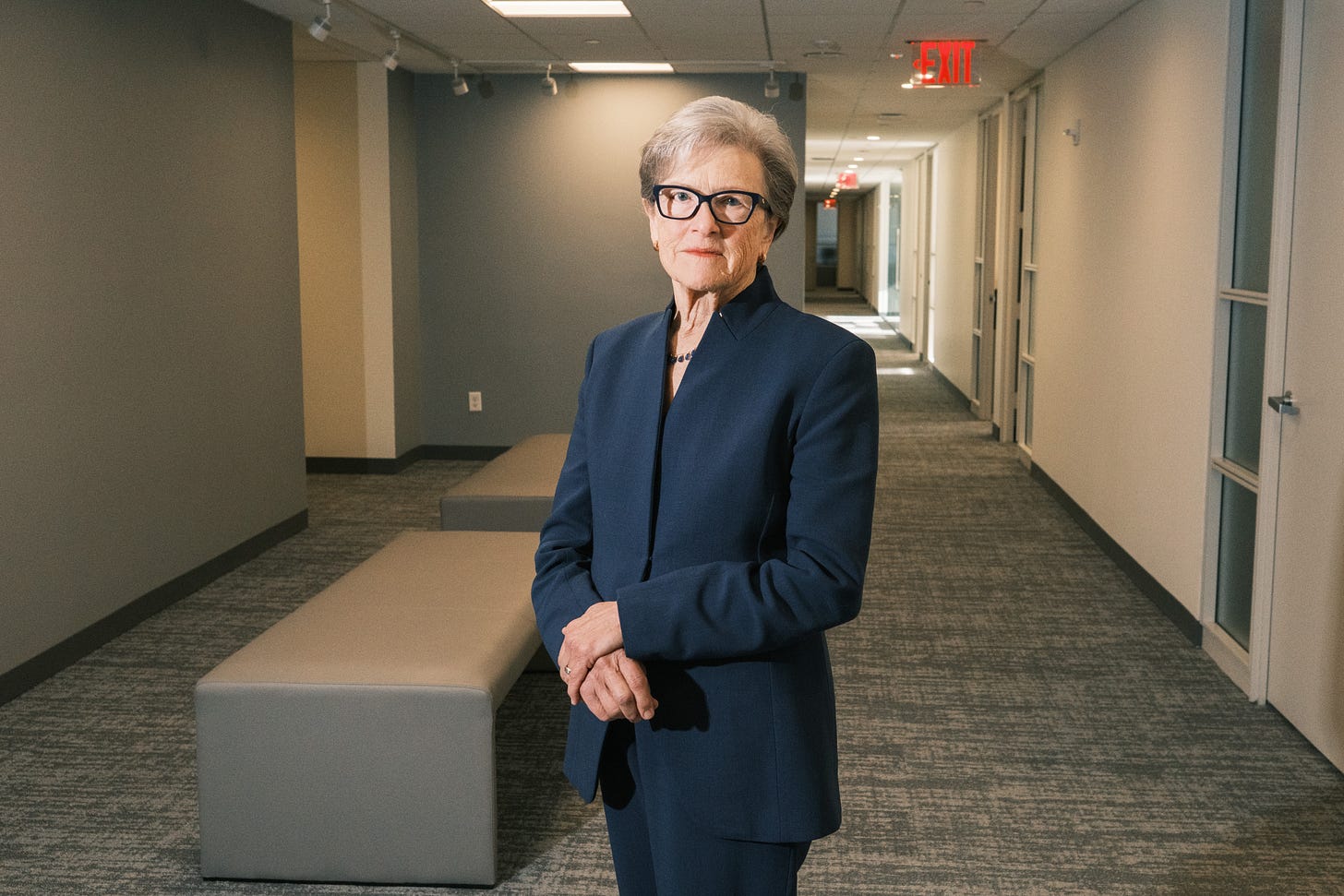

Kathryn Wylde is in the back seat of a car, working the phone as she arranges a meeting between New York City’s most powerful figures and its incoming mayor, Zohran Mamdani.

“They just offered me Monday at 11 a.m, which I’m sure is very difficult, but I need to check on his availability,” she tells the assistant to a prominent private equity billionaire.

The CEO won’t be able to make it work. Undeterred, she scrolls through the 7,000 contacts in her phone, and dials another: “Is he available to meet with the new mayor this Monday at 11 a.m?”

When the calls ends, she turns to me. “New York is about survival. If you’re around long enough, you know everybody. Half the world has worked with me in one way or another.”

She’s not exaggerating. I shadowed Wylde over the course of several weeks for this story and spoke with more than 20 people who have worked with her, sparred with her, or relied on her during some of the city’s most consequential moments.

Wylde, who turns 80 in June, is one of the most connected and influential people in New York. She is in regular contact with financial titans like JPMorgan Chase CEO Jamie Dimon, KKR co-founder Henry Kravis, and BlackRock CEO Larry Fink — leaders who shape the city’s economic and political landscape behind closed doors.

Wylde joined the Partnership for New York City in 1982 and became CEO in 2000. Founded in 1979 by David Rockefeller, the Partnership brings together top business leaders to work alongside the government to shape the city’s future. Its 350 members span Fortune 500 CEOs, tech founders, and real estate heavyweights whose companies employ about one million people in New York City. Membership is by invitation only, with annual dues ranging from $25,000 to $125,000 depending on a company’s size and industry.

As a longtime New Yorker, Wylde has witnessed the city’s most dramatic transformations firsthand, including the 1975 fiscal crisis, the financial boom of the 1990s, the devastation of 9/11, and the economic upheaval of the COVID-19 pandemic. Through it all, she has been a key figure in shaping how New York’s business community responds to crisis and recovery.

As wealthy New Yorkers fled the city during the pandemic, Wylde sounded the alarm. With crime rising, budget shortfalls looming, and left-wing politicians proposing higher taxes on billionaires, she warned that pushing away the city’s wealthiest residents could be disastrous.

Five years later, those fears now have a name: Zohran Mamdani.

Subscribe here to receive longform profiles of the world’s most successful people.

Wylde arrives at an office building in Hudson Square looking every bit the seasoned power broker. She’s wearing a dark gray blazer and matching pants, a crisp white blouse, black loafers, and a single strand of pearls. Her Coach bag carries a “We Love NYC” sticker from a campaign she helped craft to revive morale after the pandemic.

She takes her seat at a long conference table with a group of uneasy executives at her final board meeting of the Partnership’s investment fund. The threat keeping them up at night is Mamdani, the 34-year-old mayor-elect who campaigned on raising taxes on the wealthy, freezing rents, and launching city-run grocery stores. To the business community, his agenda signals higher costs, thinner margins, and a potential exodus of capital and talent.

Twenty members have convened to review new investment deals, but the conversation keeps returning to Mamdani. One executive asks: “I’m really concerned. Do you think he’ll actually do what he says?” Another chimes in: “You’re close with Governor Hochul. Will she stand up to him?”

Wylde answers with the authority of an insider. Her responses often start with, “What I was told by someone on the inside…” or “I just got a text from a CEO who never puts anything in writing…”

Though she raises concerns — especially about Mamdani’s inexperience — she speaks about him with surprising warmth. She tells the room that he’s smart, charismatic, and he wants to do a good job. Although she opposes additional taxes on the wealthy, she supports his focus on property tax reform and expanding affordable housing.

Later, as we’re walking out, I ask why exactly she likes him. It’s an obvious question for someone who once called herself “the lone defender of billionaires” while Mamdani has said billionaires shouldn’t exist. “I like his positive energy,” she begins, but her phone rings before she can finish.

For Wylde, that balancing act has only grown more complicated. At a time when the role of wealth in shaping cities is under fierce scrutiny, Wylde’s influence remains as relevant as ever, even as her retirement approaches. Her story reveals the paradox New York has always grappled with: a city built on capitalism yet constantly challenging the power dynamics that sustain it.

“Ten percent of my job is serving the members of the Partnership and 90 percent of it is serving the rest of New York City,” she says. “It’s about leveraging the contribution of the business community on behalf of all New Yorkers.”

That framing helps explain the twist that followed. After a quarter century as the leading voice for New York’s business elite, Wylde was tapped to serve on Mamdani’s transition team as one of the people he wanted to help him think through the handoff.

In January, Wylde will step down from the Partnership and the role she has occupied for a generation — just as the new mayor prepares to take the city in a very different direction.

To understand how Wylde became the unlikely bridge between New York’s corporate titans and a Democratic Socialist — and the six mayors before him — you have to start where she did.

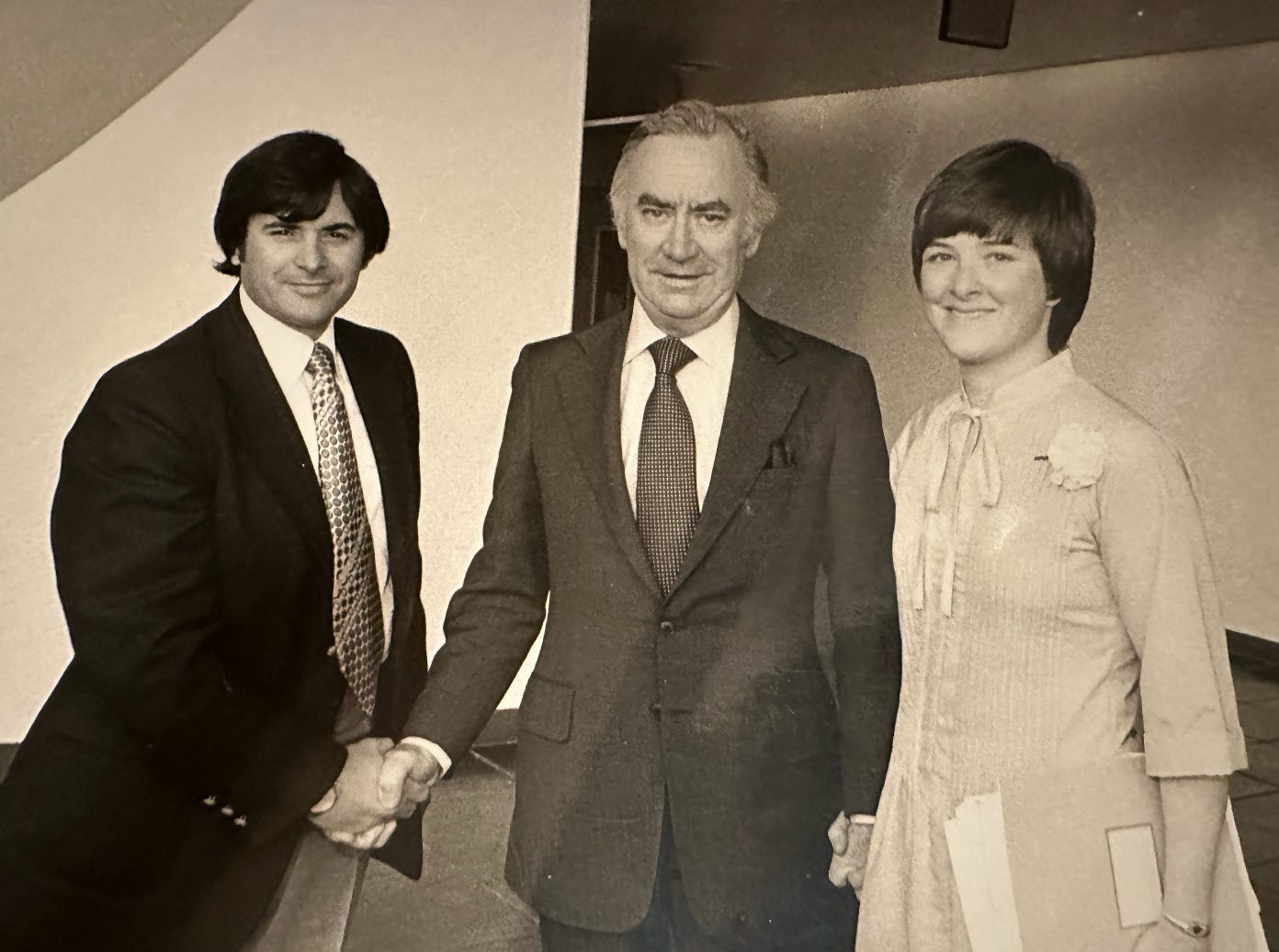

It’s hard to imagine now, but Kathy Wylde was once considered a communist in New York City political circles. She graduated from St. Olaf College, where the Civil Rights and anti-war movements shaped her early instincts for activism. When she arrived in New York in 1968, she became the director of public and community relations at Lutheran Medical Center in Sunset Park, Brooklyn.

In that role, she found herself mediating tensions between the hospital and a growing Puerto Rican community — tensions that often erupted into protests over jobs and respectful treatment in the emergency room. There, she discovered a knack for winning people over and finding common ground.

At one such protest in 1971, a man named Wilfredo Lugo showed up at Lutheran Medical Center to protest the very institution where Wylde worked. “The administration of the hospital used her to keep us in line,” he says. His first impression? She was tough, and strikingly pretty. They started talking, formed a relationship, and he became her husband. Fifty years later, they’re still together.

Wylde soon became a community organizer fighting to save Sunset Park from municipal neglect. She led sit-ins and marches, pushing federal agencies to reinvest in the neighborhood. Michael Long, then head of New York’s Conservative Party, dismissed her as a communist. She laughs about it now because they later became friends — more proof of her ability to win over even her toughest critics.

As Wylde worked to revive struggling communities, one pivotal experience in 1972 showed her that protests can generate attention, but money drives outcomes.

Twenty-six years old at the time, Wylde was helping lead a takeover of 26 Federal Plaza, home to the Federal Housing Administration. Activists were protesting a $200 million mortgage-fraud scheme that had ravaged Sunset Park. It was a predatory system in which FHA officials, real-estate brokers, lawyers, and appraisers falsified credit records, inflated prices on dilapidated homes, and targeted Puerto Rican families. When those families defaulted, banks foreclosed and flipped the homes again.

Wylde and a group of demonstrators — many of whom she recruited from a drug-rehab program — staged a sit-in in the office of Bill Green, the regional HUD administrator. “The paddy wagons were circling below, but Bill Green didn’t want to arrest us,” Wylde recalls. “At the end of the day, he gave us his written pledge that he would turn these FHA-foreclosed properties over to a nonprofit group.” (True to form, Green would later become a friend.)

It was a victory until she realized she had no plan for what came next. “We had to figure out what we were going to do with these buildings when we had no money,” she says. “I learned that it doesn’t do any good to win a protest if you don’t have the resources to turn it into housing.”

That realization came just as David Rockefeller was forming the Partnership for New York City, a coalition of business leaders working with government and the civic sector on the city’s economic and housing challenges.

Wylde was hired in 1982 to spearhead an initiative to rebuild the city’s vacant lots. She developed a program that transformed those lots into more than 40,000 affordable, owner-occupied homes and apartments across the five boroughs. In the 1990s, she partnered with private equity billionaire Henry Kravis and real estate magnate Jerry Speyer to launch a $130 million fund that backed early New York City tech startups and entrepreneurs.

Over time, she evolved from a social activist into an advocate for pro-growth, business-friendly policies. In 2000, Wylde was named CEO of the Partnership, and became the rare figure who could bridge Wall Street and City Hall.

Her trajectory from activist to power broker is unusual. How does she respond to those who say she went from protesting the establishment to enabling it?

“I haven’t changed,” she tells me. “I’ve always used whatever tools were at my disposal to pursue an agenda, and that agenda has been to create a level playing field where people who have talent and energy and want to be successful have the opportunity to do so.”

It was a tidy answer, one that didn’t fully answer my question. But the more time I spent with Wylde, the clearer her story became. She came of age professionally as New York faltered in the 1970s, when more than a million people fled, neighborhoods deteriorated, and the city hovered near bankruptcy.

That experience shaped her worldview. She seems driven less by a sweeping vision than by an aversion to disorder. She understands how fragile a city’s systems can be, and she’s determined to be the steady, connective tissue that helps hold them together.

A story from that period captures Wylde’s understanding of how to wield influence, and the responsibility that comes with doing so.

One Christmas, Wylde was baking for her annual holiday party with a close friend, Lindsay Newland Bowker, who has known her since the 1970s. The cookies were elaborate, carefully shaped, and intricately frosted. But one of them wasn’t quite perfect. Newland Bowker told her: “Nobody will notice once it’s on the tray.”

To which Wylde responded: “People only see the cookie they get.”

That sensibility was there from the beginning. Newland Bowker says Wylde wasn’t like the other activists. She was a strategist. “Kathy just looks at a complex problem and sees the whole of it,” says Newland Bowker. “She sees the cause, she sees the consequence, and she sees who is necessary to create a solution. That’s her magic.”

That theme surfaced again and again in my conversations with people who’ve known her for decades. They told me Wylde’s goal is to move everyone toward a solution and a sense of order instead of getting caught in the politics around it.

“She’s focused on a positive outcome and not on ideology,” says Maria Gotsch, the head of the Partnership’s investment arm who has known Wylde for 25 years. “It’s about, ‘What is best for New York City, what’s the problem we’re trying to solve, and who are the people that we need around the table?’”

When Wylde began to understand that cities are rebuilt not by ideology but by coalitions, she discovered she had an unusual ability to speak both languages. This marked the beginning of her transformation from protester to power broker.

A hundred of New York’s most influential women — executives, industry leaders, and public officials — file into a glass-walled dining room on the 39th floor of Citibank’s Tribeca headquarters. The room is called “The New York,” and it lives up to the name. Across from the podium, the windows open to an unobstructed view of the Freedom Tower.

Citibank CEO Jane Fraser opens the program by turning to the woman standing in front of that skyline, Kathy Wylde. “There has been no stronger partner between the public and private sector than yourself,” she says. “All of us will continue to lean on you in the years ahead. So it’s certainly not a farewell, and—”

Before she can finish, Wylde jumps in with impeccable timing. “I’m retiring, I’m not dying,” she deadpans. “I feel like I’m at my own funeral.” The room erupts in laughter and applause.

Next up is New York Governor Kathy Hochul. “When I became governor, people told me that if I wanted to understand New York City, I needed to know Kathy Wylde,” she says. “I now know Kathy, so I guess I know New York City.”

What Hochul doesn’t say on stage — but tells me later — is that Wylde backed her long before she became governor, meeting with her when she first ran for Congress in 2011 and opening doors she couldn’t yet open herself. “One of her callings is to be a mentor for women,” Hochul says. “I bet no one can count how many women have benefitted from her interest in them personally and in their careers.”

Wylde moves through the event with the ease of someone who has spent decades choreographing the city’s public-private dance. She introduces each speaker and keeps the agenda moving. When one CEO’s speech runs long, Wylde steps forward with her hand outstretched for the mic. “I’m still in charge,” she says with a smile.

When I ask how she defines power, she doesn’t hesitate. “I was a political science major, and I was very interested in power and how decisions were made,” she says.

One book that stayed with her is Moral Man and Immoral Society, which argues that institutions aren’t moral actors — individuals are. “They’re not good or evil,” she says. “They’re instruments that individuals use to influence society.”

She subscribes to Robert Dahl’s theory of pluralism, which posits that influence is scattered across many groups, not concentrated in one. As a young organizer, she tested that idea by asking neighbors: “Who do you turn to when you need help?” The answers — a bodega owner, a minister, a nonprofit leader — revealed the hidden map of local power. “You put those pieces together,” she says, “and you start to see the horizontal and vertical networks you can use to get things done.”

She drew on that same instinct in 2011, when New York’s Marriage Equality Act faced a tight Senate vote. Republicans wanted political cover from the business community. Wylde went to then-Goldman Sachs CEO Lloyd Blankfein and asked him to sign a letter framing marriage equality as an economic issue. “He signed the letter, and a hundred signatures followed,” she says. “If you get one person with the courage of their convictions, then everybody else lines up.”

When I asked Blankfein about it, he was blunt. “It was the logical and right thing to do,” he says. “And of course, it was very pro-business.”

That moment shows how Wylde uses power. She knows which voices matter, when to deploy them, and how to align principle with self-interest.

Others I spoke to define her power as access nobody else has, speed nobody else can match, and institutional memory nobody else possesses. Lori Lesser, a partner at Simpson Thacher & Bartlett, put it this way: “She is unique in knowing who’s who, who knows who, who knows what, and who gets what done. She can get all of those ‘whos’ to answer her call and get them all into the same room.”

Wylde carries the energy of someone at the start of her career, not the end of it. When I text her, she replies within minutes. A single day might include: a meeting with the governor; a Wall Street Journal interview about what the business community is doing to stave off the National Guard; an Al Jazeera segment on the mayor-elect; a briefing with the head of homeland security about ICE contingency planning; a reception with a Puerto Rican nonprofit; and a benefit for a national mental-health organization.

All of that access demands a pace few people can sustain.

Etsy CEO Josh Silverman told me Wylde has never taken more than 20 minutes to return one of his messages. JetBlue CEO Joanna Geraghty recalled that when the airline considered relocating, she immediately convened a cross-sector group to make the case for staying. “It was a group project,” Geraghty says. “But she’s the one who drove it forward.”

Not everyone experiences that drive as gentle. Some sources told me Wylde’s consensus-building can feel like being force-marched toward a predetermined solution. Even the most seasoned CEOs can hesitate to push back. As one Partnership member put it, “You don’t want to pick a fight with the human embodiment of an immovable force.”

I ask Wylde whether a certain ruthlessness comes with the job. “Toughness, yes. I’m sure I’ve become tougher, but I have what you could call the courage of my convictions,” she says, repeating the same language she used to describe Lloyd Blankfein’s leadership.

When I spoke with Carlton Brown, a developer who has known Wylde since the early 1990s, about how her style has changed, he explained it this way: “Early on, she had that Midwestern way of saying, ‘Oh you’ve got spinach in your teeth.’ Now she’s more like, ‘You should probably go give yourself a good look in the mirror.’”

And even with that harder edge, she can’t always pull a fractured group into agreement. The election of Zohran Mamdani marked a moment when her coalition simply wouldn’t cohere.

On Election Night, someone snapped a photo of Wylde slipping into mayor-elect Zohran Mamdani’s victory party and posted it on X. The image feels almost paparazzi-esque — a powerful figure caught on a New York City street, moments before stepping into a venue charged with political meaning.

Mamdani came out of nowhere and captured the city’s imagination with flashy campaign videos and youthful charisma. The 34-year-old Democratic Socialist promised free public transit, universal childcare, city-run grocery stores, a higher minimum wage — all funded by taxing corporations and the wealthy, policies Wylde has long warned against.

My question was obvious: Why did Wylde, the woman who spoke for the business elite, show up at Mamdani’s celebration?

Her response was characteristically polished: It’s her job, she told me. Mamdani is the person New Yorkers elected. “We work with whoever wins no matter who they are,” she says. (Wylde described herself as a centrist Democrat who did not vote for Mamdani in the primary but did support him in the general election.)

She added that he “picked the right issues,” including housing affordability, which Wylde calls one of New York City’s most complicated challenges. Wylde is drawn to problems that seem unsolvable and to building the underlying systems that make them work. Even where she disagrees with Mamdani’s policies, she is uniquely positioned to help translate his goals into action by collaborating with the private sector.

Mamdani called her two days after the primary to ask which business leaders he should meet. Wylde organized several meetings — including one tense session at the Partnership moderated by Pfizer CEO Albert Bourla and Tishman Speyer CEO Rob Speyer — where Mamdani faced a barrage of pointed questions.

Ahead of the primary, Wylde appeared on CNBC’s “Squawk Box” as voters headed to the polls. “Terror is the feeling,” she said of how the business community viewed Mamdani’s rise. But as his victory grew more certain, her tone shifted. She noted that he’d added nuance to his proposals and was willing to listen.

When I asked her if she believes that billionaires should exist, she saw where the question was headed and beat me to the punch. “It’s not anybody’s job to say they should or shouldn’t exist,” she says. “I interpreted Mamdani’s statement that ‘billionaires should not exist’ as being a protest of wealth inequality. I didn’t interpret it in a literal sense.”

On Nov. 24, Mamdani announced that Wylde would join his transition team as he prepared to take office on Jan. 1, 2026. Some saw her inclusion as a welcome signal that the new mayor valued a pro-business perspective. “Any incoming mayor who doesn’t put Kathy Wylde on his transition committee would have to be out of his mind,” MTA CEO Janno Lieber told me.

Others saw it as a betrayal of the very community she was representing. Andrew Ross Sorkin opened a “Squawk Box” segment about Mamdani’s transition with an unmistakable jab. “For the last couple of months, we’ve had Kathy come on the broadcast representing the Partnership for New York… and she would be more supportive of him on our broadcast than the text messages and emails I was getting from the membership of the Partnership,” he said. He added that she had not disclosed she would “go work for the Mamdani administration,” and he had wished she had.

Wylde maintains she isn’t taking an official role, only offering to advise “to the extent he wants my advice.” Mamdani could not be reached for comment.

During her career at the Partnership, Wylde has worked with mayors Edward Koch, David Dinkins, Rudy Giuliani, Michael Bloomberg, Bill de Blasio, and Eric Adams. Now, as she prepares to step down, New York is shifting under her feet, and the next mayor is unlike anyone the city has ever seen.

At the entrance of 30 Rock’s storied Rainbow Room, Wylde takes her post, greeting members of the Partnership as they step off the elevators and into the glittering hall where the annual meeting is about to begin. It will be her last as CEO.

A line forms almost immediately. Everyone wants a moment with the woman who has welcomed them this same way for 25 years. The man in front of me grabs her hand and says, “Thank you for everything.” Wylde smiles and shoots back, “Come on, this feels like my swan song.”

In attendance are some of New York City’s most elite dealmakers and CEOs, including IAC chief Barry Diller, Santander Bank CEO Christiana Riley, and Pfizer CEO Albert Bourla. “Kathy will leave a legacy as one of New York’s most influential civic leaders,” Bourla told me, calling her “a force.”

The keynote speaker is New York City Police Commissioner Jessica Tisch, who began her remarks by thanking Wylde for her guidance, counsel, and support. “I have worked in city government for 18 years now, and Kathy raised me from the beginning,” she says.

When Wylde steps up to close the program, she keeps it simple: “Thank you all. After 43 years, this is my last annual meeting, but I’ll be around.” She gets a standing ovation.

When I ask her why now is the right time to retire, she answers with her signature pragmatism: “I’ll be 80 in June, and my life expectancy is around 88. Plus, I haven’t had any time for myself in 50 years.”

I assumed that retirement meant she would finally slow down and even settle into a quiet life in Puerto Rico, where she and her husband have had a home since 1981.

I was wrong.

People close to her can’t picture Wylde easing into anything resembling leisure. Her friend of 15 years, fashion entrepreneur Deirdre Quinn, told me that even Puerto Rico can’t lure her into relaxation. “We were at her pool, and I asked her where the lounge chairs were,” Quinn says. “And Kathy looks at me and goes, ‘What lounge chairs? I don’t lounge.’”

It’s a mindset her network has come to rely on. “I think all of us are anticipating that we’ll call her as frequently as we do now,” Warby Parker CEO Neil Blumenthal tells me.

Wylde winces whenever I ask about her personal life — her childhood, her downtime, anything that doesn’t involve work. But one story slips through.

As a child she had a neighbor who regularly gave cookies to the kids on the block. Wylde loved cookies, so one day she cut another neighbor’s flowers, brought them as a “gift,” and tried to barter for more. The woman saw her snipping the flowers, told her mother, and young Kathy ended up in big trouble.

“It was a good reminder that actions have consequences. All of us tend to remember every wrong thing we’ve ever done,” she says of something that happened 76 years ago.

She applies that lesson just as rigorously to her professional life. She recounts a time when she criticized Mayor Michael Bloomberg’s education policy in the press. Word reached her that he was “very annoyed,” so she asked to meet, apologized, and repaired the relationship. The experience taught her a rule she still lives by: disagreements should be handled privately, not aired in public.

Her friends tell me that Wylde has always had this level of discipline and conscientiousness. They fill in the rest: she’s a talented baker, animal lover, and fast driver. “Kathy drives a car like she drives New York,” Quinn says. When I mention these details to Wylde, she shakes her head. “Who told you that?” she says. “Must have been Deirdre.”

So what does she plan to do in retirement? For the moment, her intention is to support the efforts of mayor-elect Mamdani, Governor Kathy Hochul, and the Partnership, continuing to lend her experience where it’s needed.

Martin Lipton, the lawyer who helped save New York City from bankruptcy in 1975, told me he’s deeply concerned about the city’s future without her. “Kathy is, in my opinion, absolutely unique, and while I hope her successor is successful, I’m very concerned about the future,” he says.

Steven Fulop, the outgoing mayor of Jersey City, will take over as CEO of the Partnership in January. He told me he’s under no illusion about the scale of what he’s inheriting — “there will never be another Kathy” — and that his approach will differ from hers. He wants the organization to take more public positions and be more explicit about which political decisions help or hinder the business community.

Fulop says Wylde has been candid with him about the Partnership’s future. “She recognizes that my fate and her legacy are intertwined,” he tells me.

When I ask if she has one piece of advice for him, she doesn’t hesitate. “I hope my successor understands that in New York, power comes from the bottom up, not the top down.”

Her next chapter remains undefined. “I’m at a point in life at which you start counting backwards,” she says. “You start asking: ‘How much time do I have, and what do I want to do with every hour of my day?’ I’ve had no discretion over that for 50 years, but now I do.”

I weave my way through the crowd that has encircled Wylde and ask her one final question: “How does it feel knowing this is your last Partnership meeting?”

She laughs, purses her lips, and shrugs. “I mean...,” she pauses, “the same.”

Then she turns back to the crowd because the room is still hers. The next person who hugs her goodbye leans in and says, “We know you’re not going anywhere.”

And they’re right. She — and everyone else — knows this is not Kathy Wylde’s final chapter.

—

Written by Polina Pompliano | Edited by Laura Entis | Photos & video by Stephen Yang